Category: Education

-

Sakina needs help

Posted on

by

Sakina’s future hangs in the balance. I first met her in Kolkata in May 2022. Tiljala SHED staff brought her to my attention at a meeting of all the evening class students at the Mir Meher Ali Lane centre in Tangra. What […]

-

-

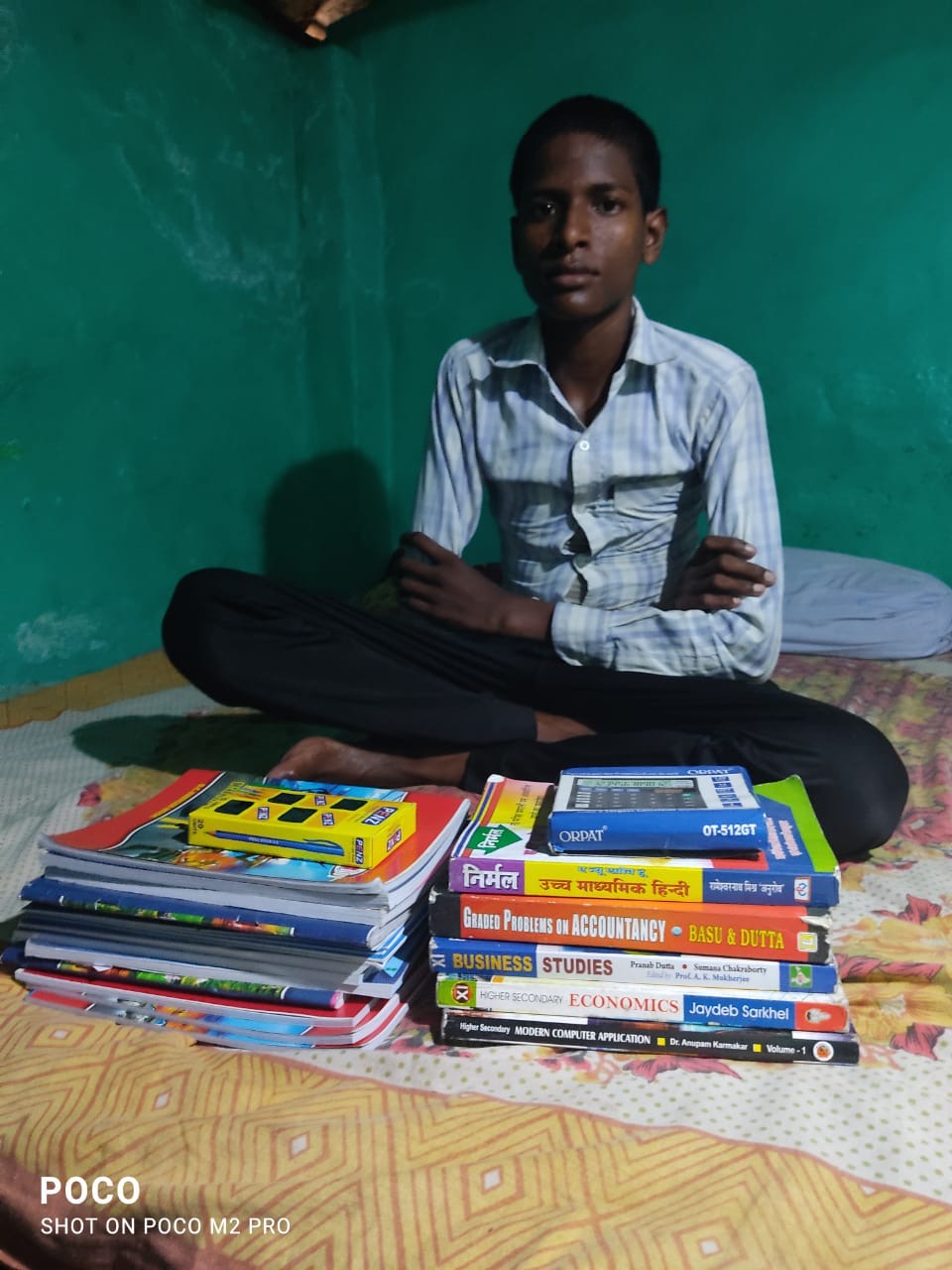

Bhola’s Story

Posted on

by

This is Bhola. He is 16 years old and lives in the Topsia canalside squatters, a row of shacks built on a spit of land in the middle of an open sewer in central Kolkata. There are two fresh water taps for […]

-

Visiting the Park Circus Children’s Club

Posted on

by

I don’t know where to begin. I have been visiting Tiljala SHED for 5 years and thought I couldn’t be surprised by anything. Yesterday I was invited to attend school. Local children from the Park Circus Railway Squatters (mostly the children of […]

-

My Experience of Kolkata’s Rag Picker Communities and Tiljala SHED’s Amazing Work there

Posted on

by

I visit Kolkata and Tiljala SHED two or three times a year. I love to catch up with old friends and spend time exploring my favourite city. But most of all I love to be part of the great work Tiljala SHED is doing […]

-

The importance of a good education

Posted on

by

Education is one of the most effective agents of change in society. When a child is able to go to school today, he or she sets off a cycle of positive change. But, thousands of children in India lack access to education […]